Dear Comrades,

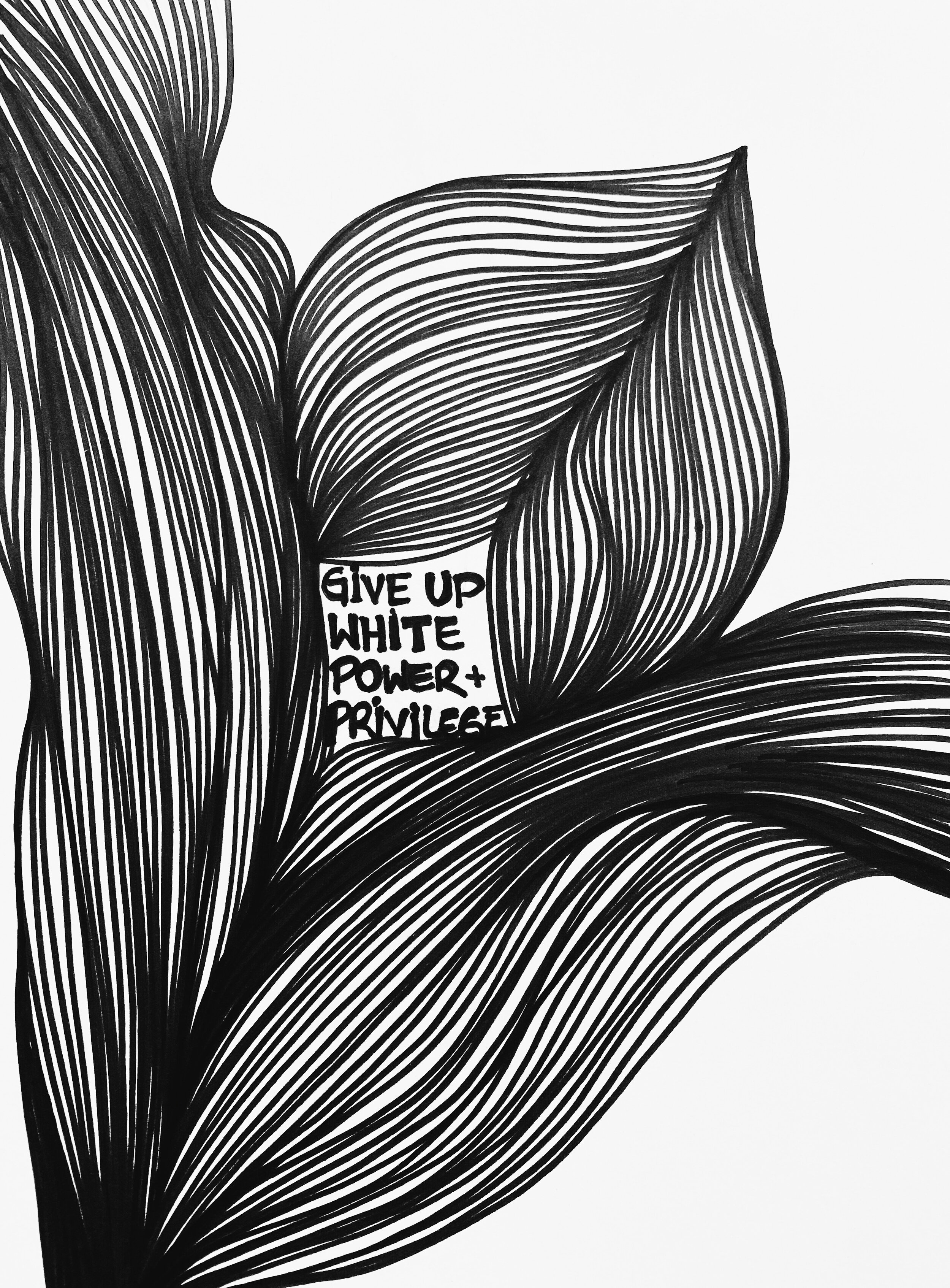

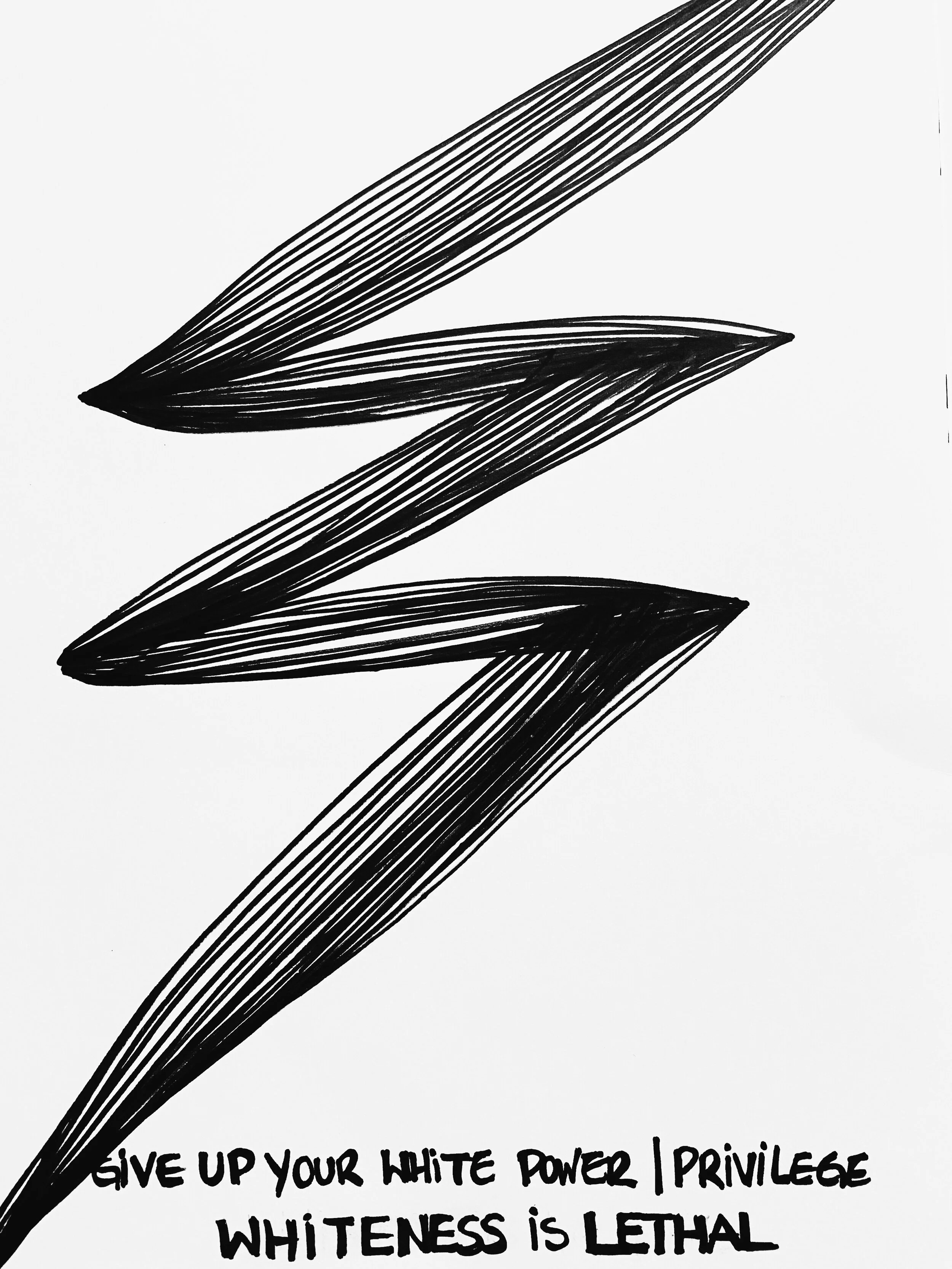

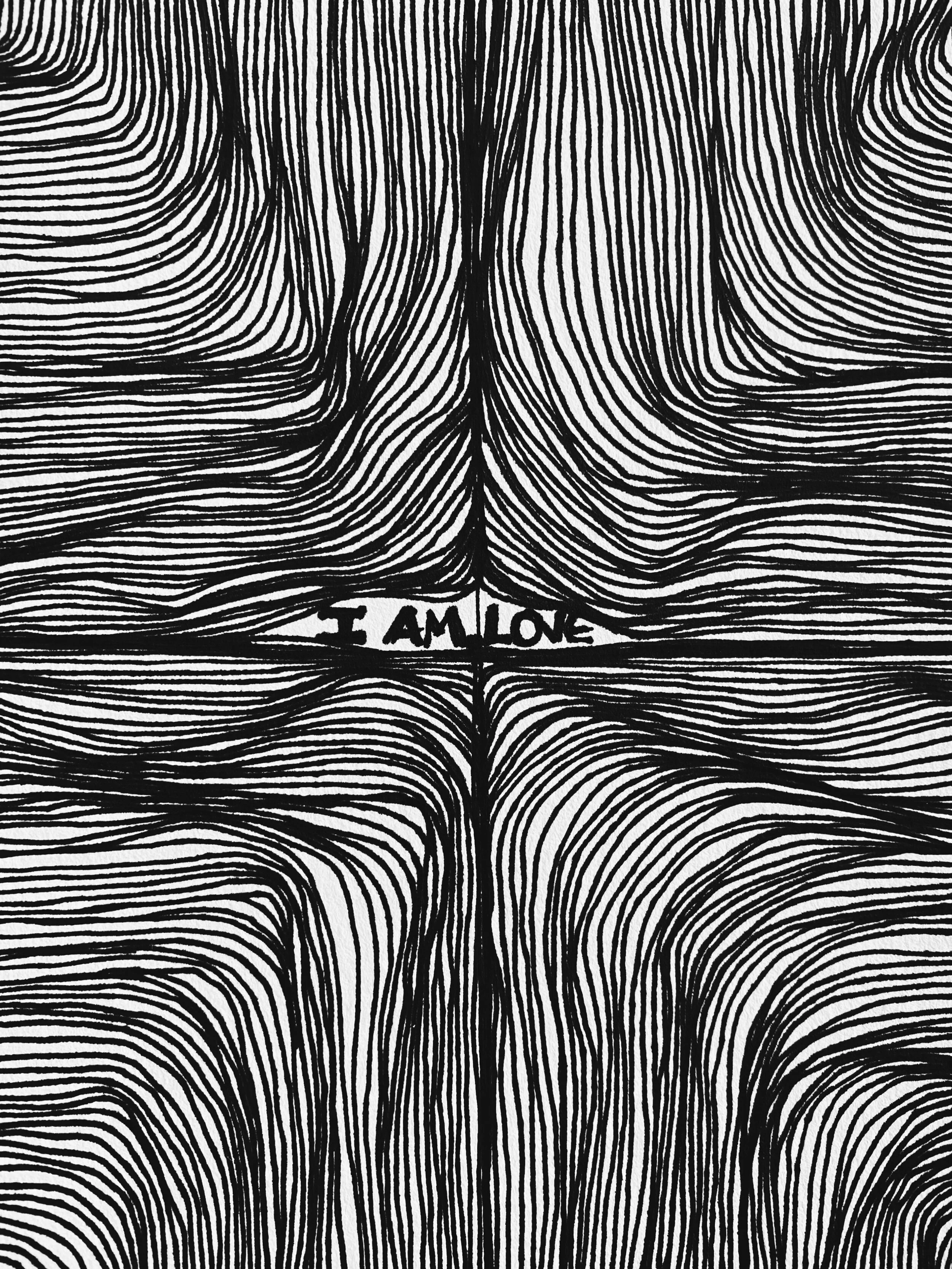

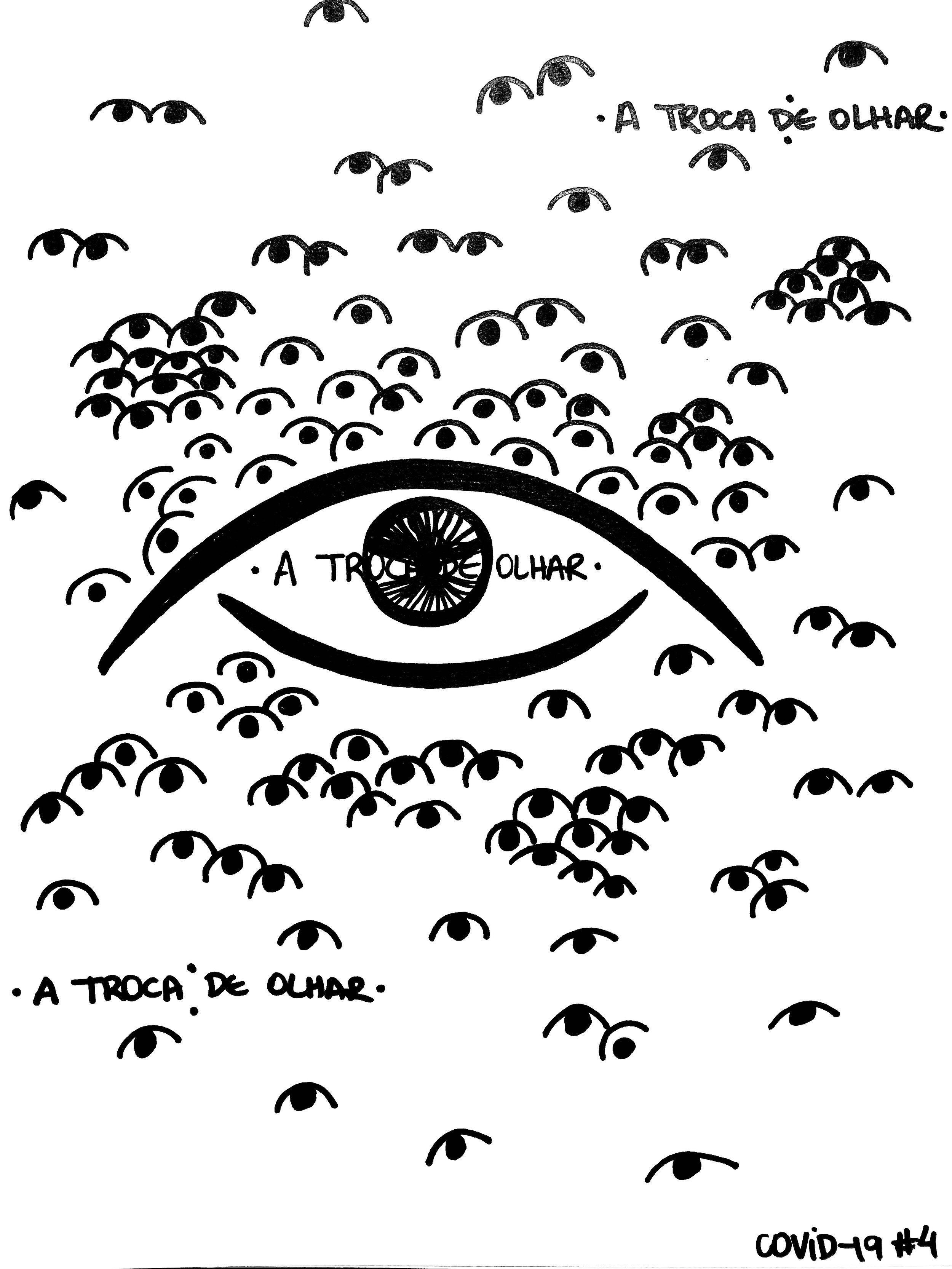

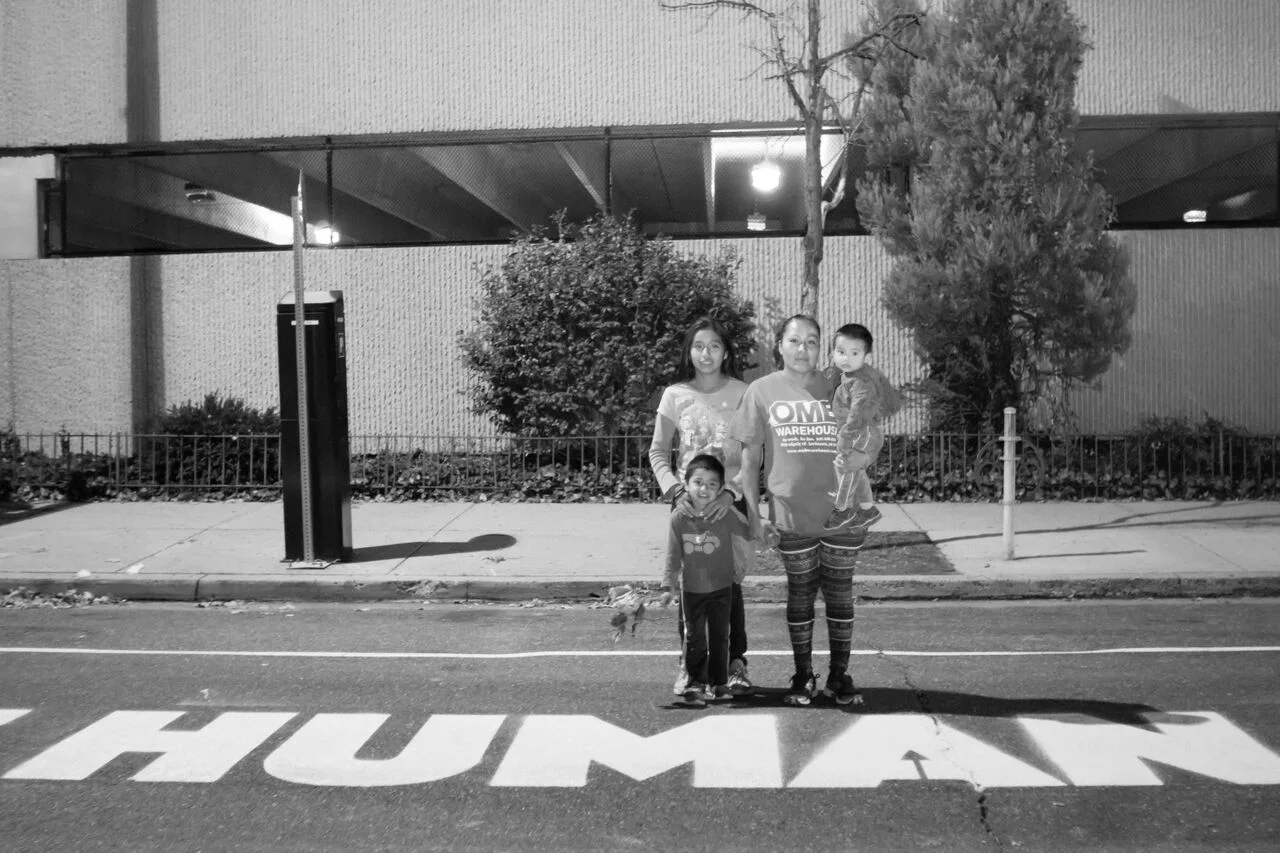

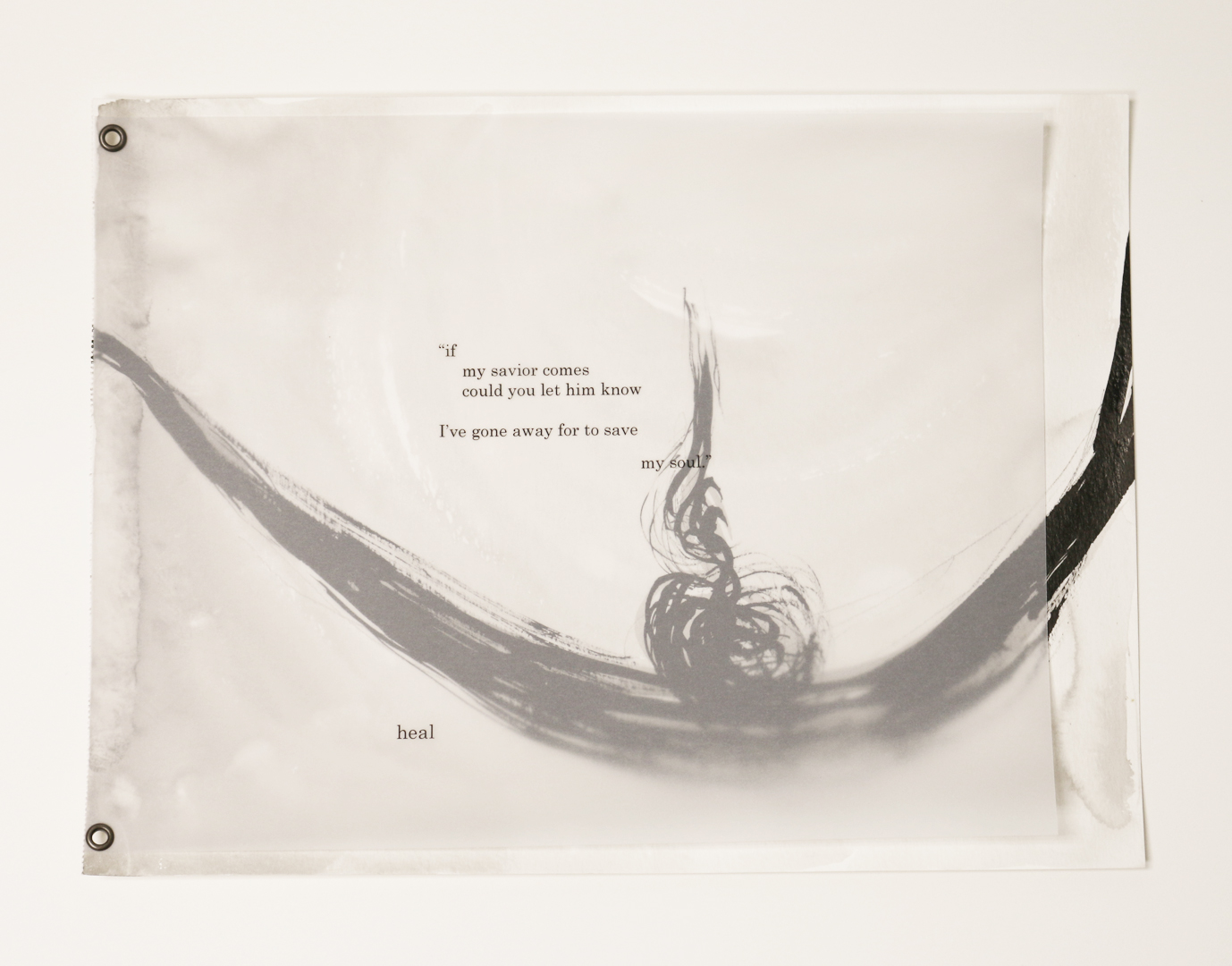

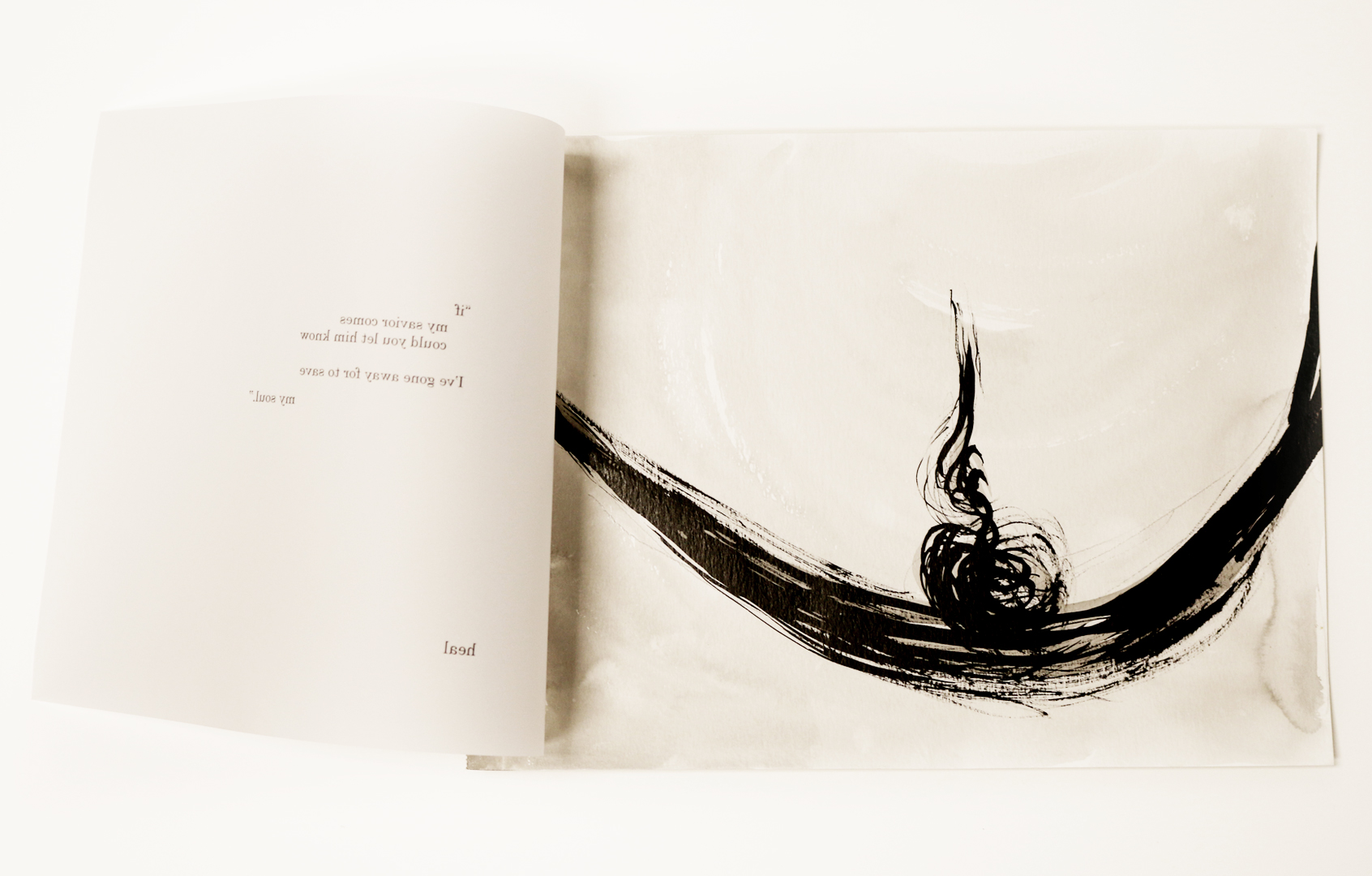

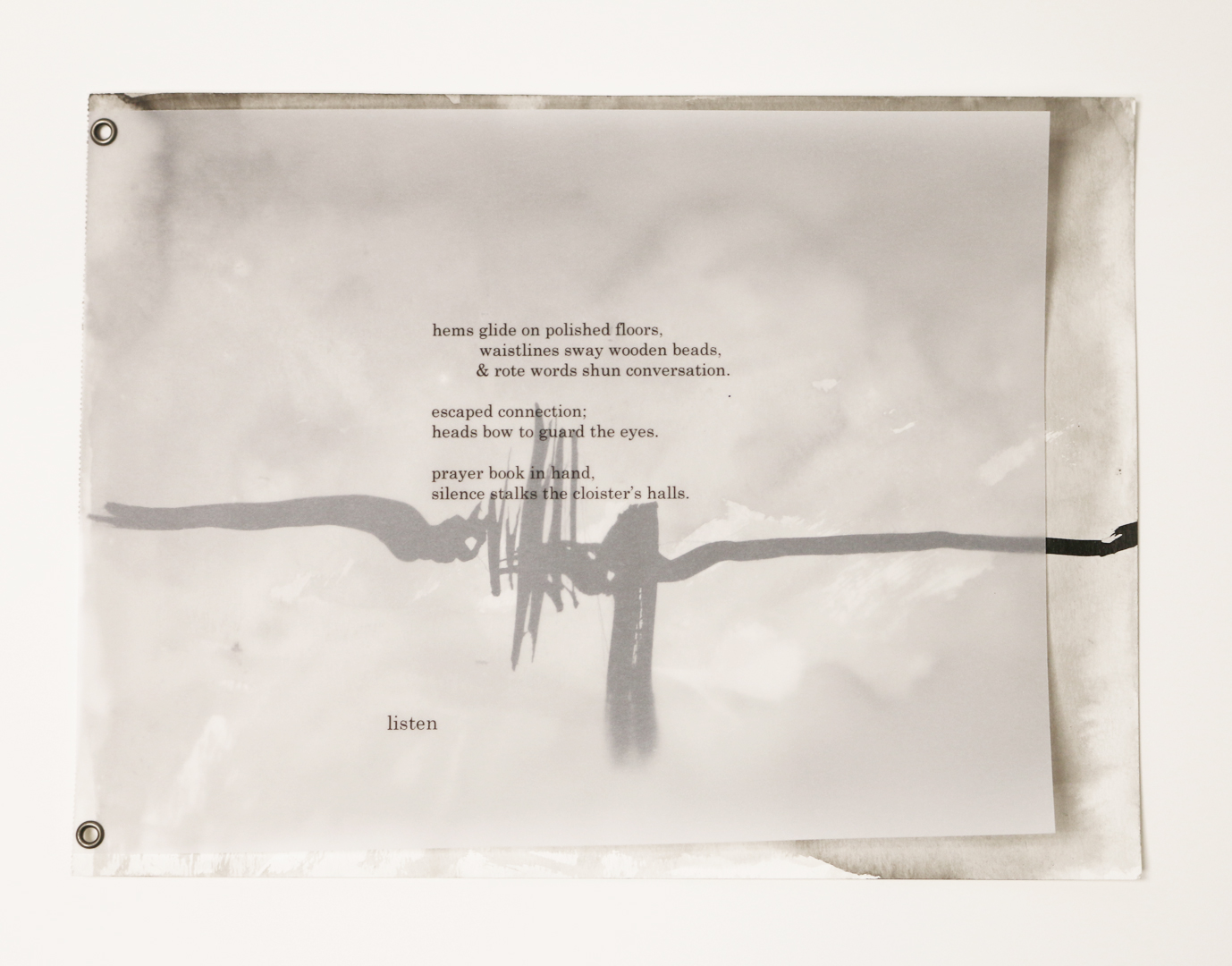

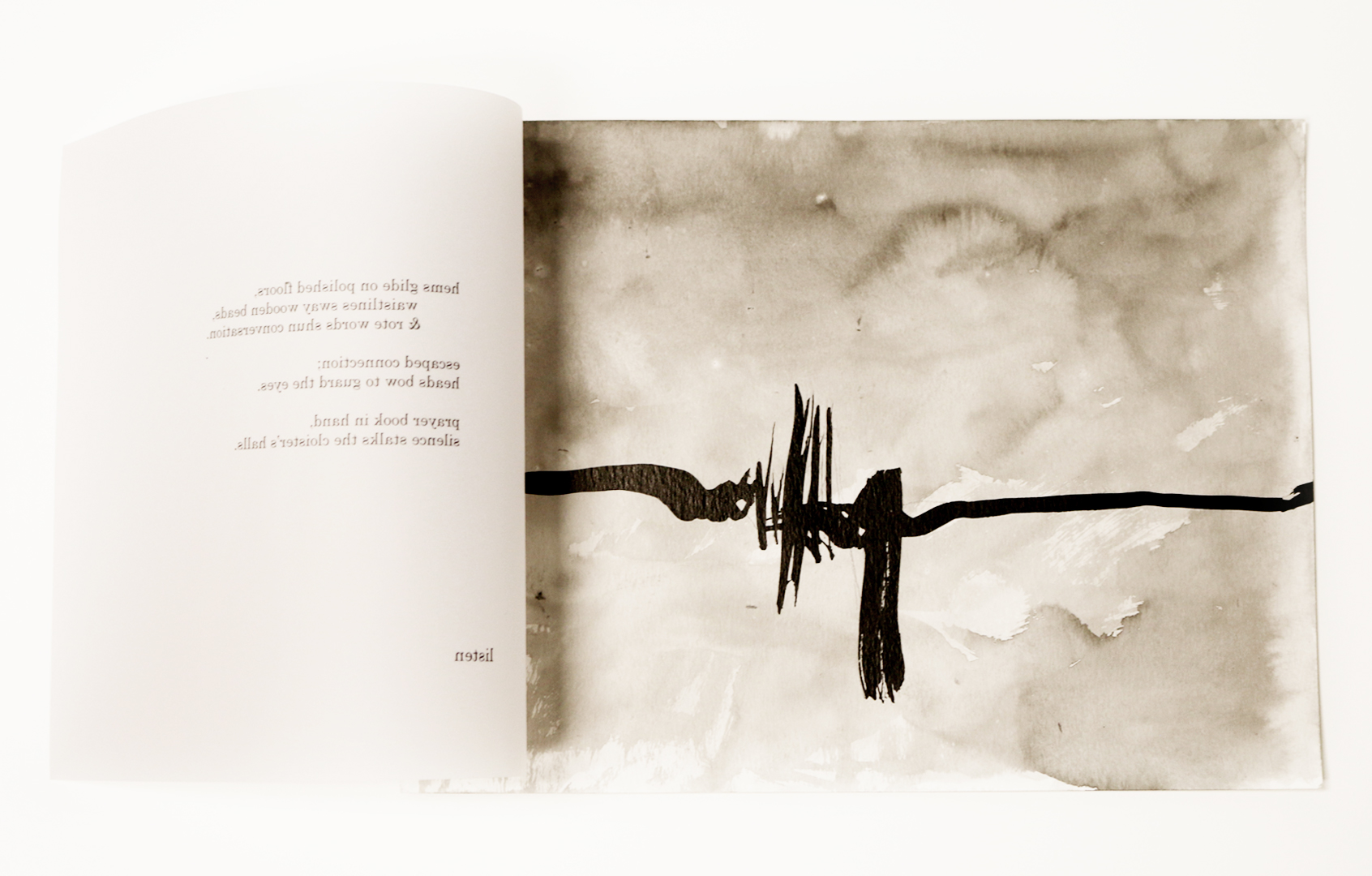

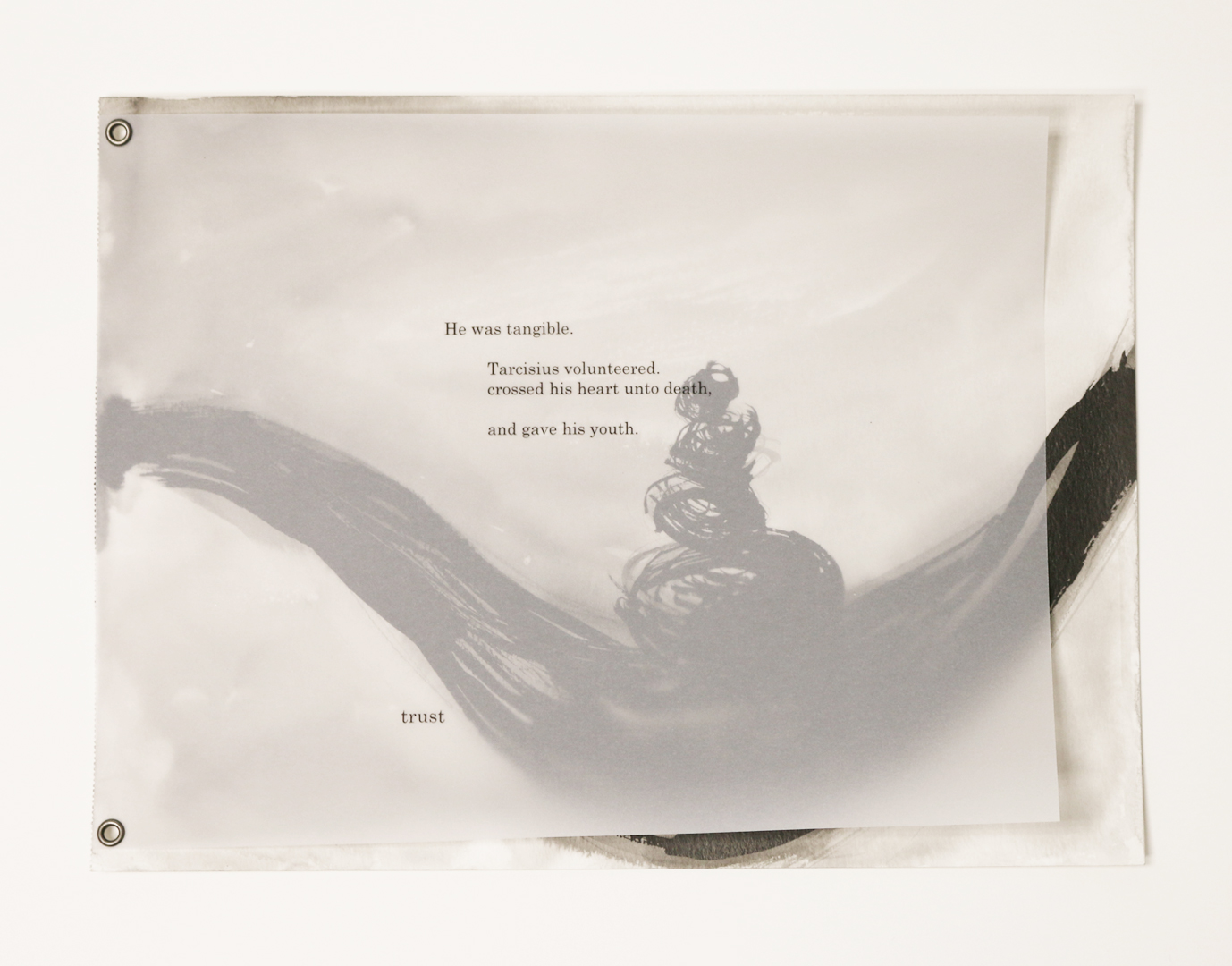

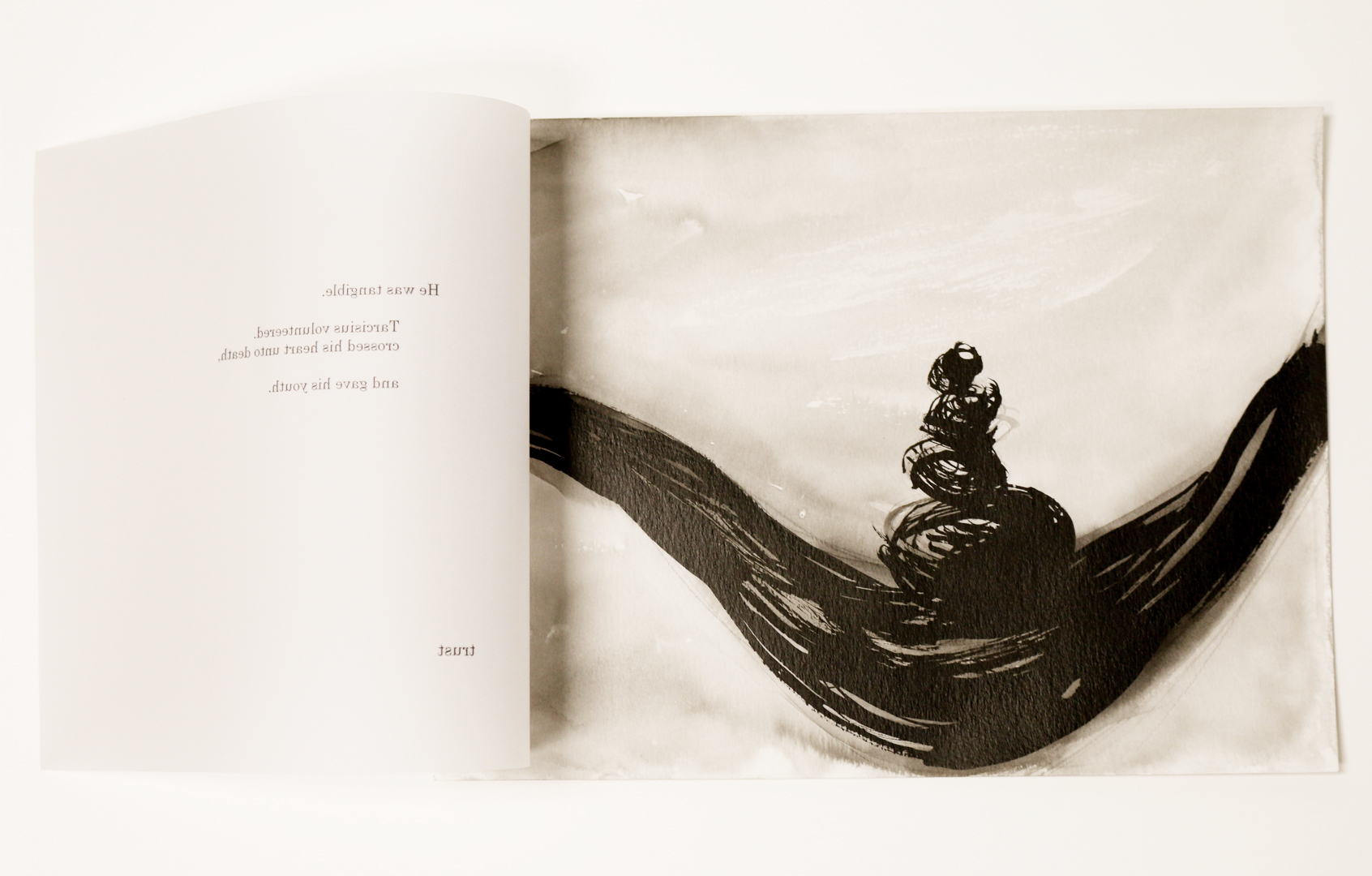

Here I am again with this urge to write to you. I hope you are fairing well since you last heard from me—my last letter went out to you about a week ago… This desire to write you this time around came from a very vivid dream I had last night. Despite its intensity and vibrancy, it seemed to be taking place thousands of years ago. The images that you will see dispersed throughout this letter were shared by a good comrade, calvin Williams, and they will perforate the weaving of these words offering yet other worlds. The land in this dream was so vast, expansive. People seemed to cross boundaries of time, space, culture, experience. I woke up thinking that McFarlane was right, after all: we must shelter what is precious in this life, dispose of what is harmful. I have been thinking that one of the ways we could engage in this is through the sheltering of our songs, our dreams, our images, our histories and the precious messages they convey.

They seem so fragile, at times, but they have enchanted many stories from our ancestors, so many peoples across this vast earth. I have also been thinking about how we are to dispose of trauma, the violences we are living through, the poison we have been given, the secrets we can’t bring into light. Those ancient people in my dream seemed to believe that words were enchanted beings that carried power. Words were enunciated with a sense of desire, of embodiment, of material fullness. It was like they could blossom into something so full of grandeur. They were uttered by way of invocation, it seems, as though they were practicing the incantation of possibility. They spoke and things would emerge: poetry, heavy magic, prayer, utopia, worlds. All of it overflowing with desire. Sorcerers they were. The folks I saw constructed their worlds through words, and those words became objects, and material expressions of love, of beauty, of laughter. It was as if that desire spoken through words had the power to gestate other possibility for the world.

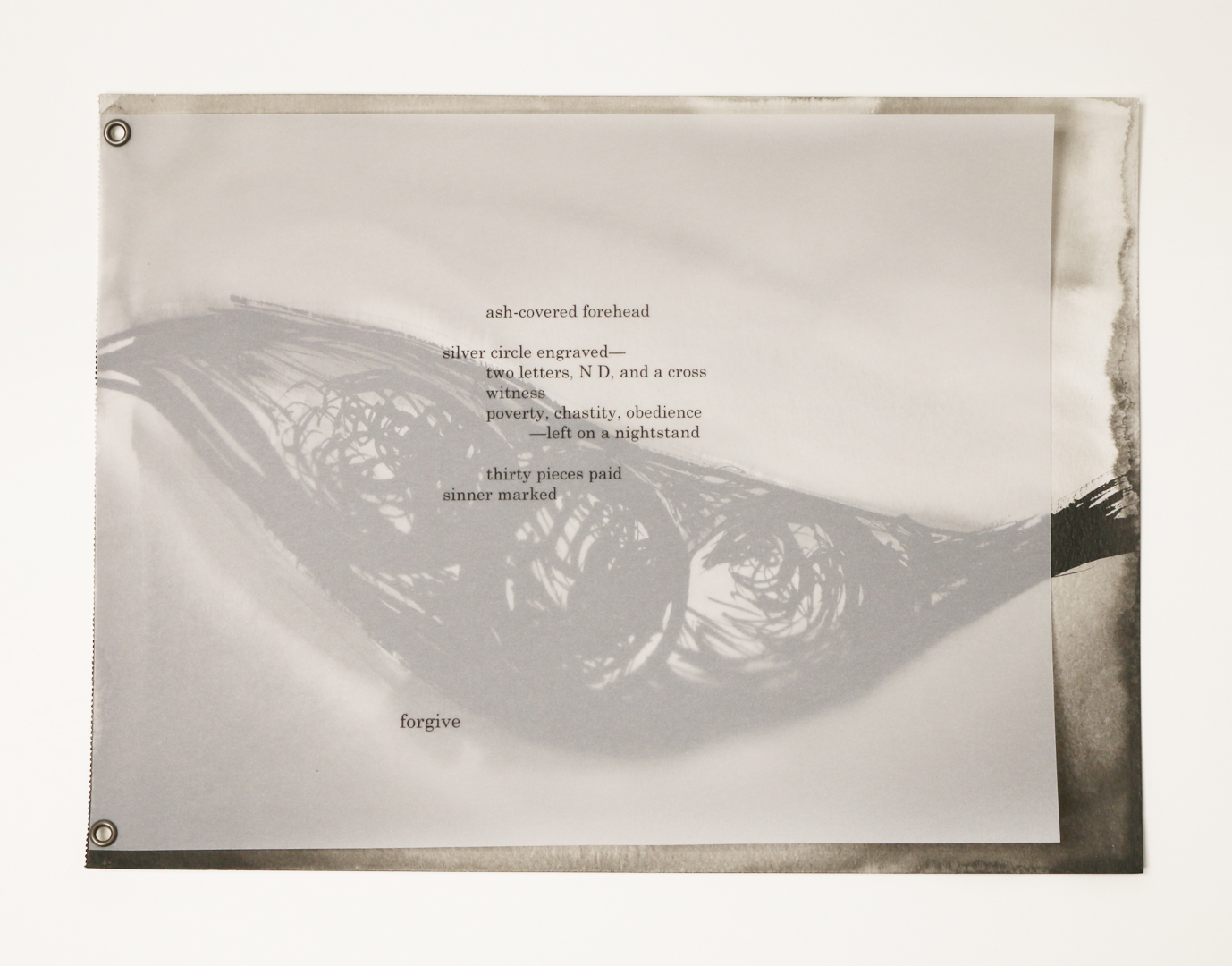

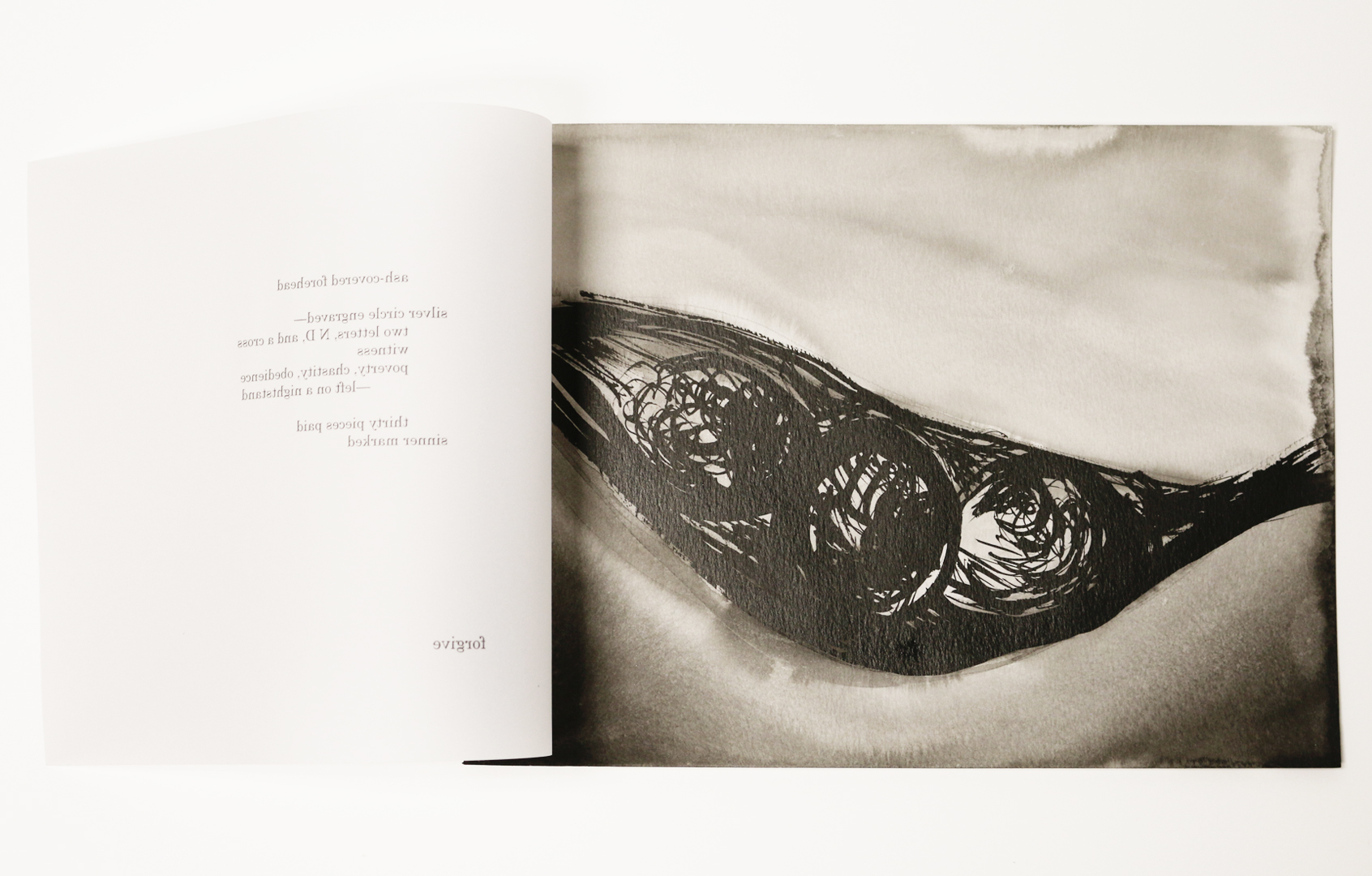

It reminds me a bit of what the theologian-poet-prophet-analyst Rubem alves says… temos que dizer o nome das coisas que nao sao pra quebrar o feitico daquelas que sao…

We must say the names of things that are not yet

To break the spell of the things that are.

One of the most vivid images of this dream is that there were people just being. This guy was walking across what seemed to be a city of dead bones. Another was watching a banana slug move from one side to the other of a leaf. Oh, there was this child laying on grass looking at the sky, and an elderly women trying not to bother bees too much as she reached for the honey. There was this other person watching the sky so intently. I don’t think I spotted any consumer “goods,” mercadorias. I think I prefer the Portuguese word here, that which is made for markets. Dressing those products with this imprudence word “goods” plays tricks on our brains. I digress. My point is: there was no shadow of profit, I think, in this dream. Lots of play, lots of desire, though, lots of being-ness, and time to contemplate beauty. I don’t recall sensing confinement there. Prisons. The doors were always open, sometimes not there at all. There seemed to be a language that spoke of interdependence, of love, of convivencia, to live with. The doing-ness was an extension of a pulsating body that inflated and created life with this earth. The dream reminded me of this idea of theopoetics, an artistic articulation of the character of God. Folks were doing what Claudio Carvalhaes told us to, to listen to the words we were never taught. To hum songs, beat drums because the words we know are unable to say what we need to convey. When night fell in this place, Folks were concerned mainly with listening to the sounds of the earth, the language of the rivers and the trees. Night wasn’t time to only recharge so that they could continue to work work work work the next day. Night was where theopoetic holy energy would surge, would be transformed into Holy presence. Like Kurt Elling sings, they seemed to be raptured by the questions like why does coal sleep in darkness, do dreams live in apart-ness? Where is the soul of water? Is love motion? Where lies the holy sparks that animates us? Holy dream, holy vision, holy scheme, holy mission. Holy one to another, holy me, holy other. Holy lives, holy blending, holy start, holy ending.

People in this dream I am describing to you, dear comrades, were dreaming better dreams at night… not of themselves, as Brazilian Yanomami shaman Kopenawa warned us… They were engaging with what Ailton Krenak was suggesting we do: to reach for the imaginative capacity that Indigenous peoples have been sustaining since first contact: the pleasure of being alive,

of singing,

and dancing together,

of tolerating pleasure, and the fruition of life,

of not giving up on dreams,

and of dreaming better dreams that are capable of postponing the ends of the world, for it has ended and reemerged numerous times for those who have survived colonizers.[1] On of the most profound teaching Indigenous cosmologies can offer us is to holify, sacralize our relationship to the world, to teach us how to exercise an ongoing reverence to the earth and all our relations. Like that spider I told you last week, our ways of being, according to indigenous scholar Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, needs to be spun out of an expansive “web of connections to each other, to the plant nations, the animal nations, the rivers and lakes, the cosmos, and our neighboring Indigenous nations,” in what she describes as an ecology of intimacy.[2]

How do we think with our whole bodies and develop a more capacious understanding of siblingship, of kinship? The ancestral relations I saw in this dream were the fruits of a living that was based on “deep reciprocity, respect, noninterference, self determination, and freedom;” on a knowing that “the earth gives and sustains all life” and that “natural resources are not natural resources at all, but gifts from Aki, the land.” According to Anishinaabeg teachings, we should “give up what we can to support the integrity of our homelands for the coming generations. We should give more than we take from it.”[3] This is a movement that radiates outwards and inwards in a “rebellion of love, persistence, commitment, and profound caring.” Working together to “create constellations of co-resistance,” radical alternatives are found and which are based on reciprocity, community, and refusal of lethal colonial projects and all its iterations.[4] And for that, people of this dream seemed to be working, to create myths and languages of presence and love. First love, then knowing. Knowing, as Alves says, is erotic, it becomes impregnated, and it needs desire so that bodies can move towards love, towards care, towards embodied fluidarity (as Catherine Keller once put it), and towards balance, justice. What stories are we telling ourselves? What myths are we embodying and what do they reflect about our desires? When I think about this dream of people living thousands of years ago, I am saddened. Myths of love seem to have escaped us. We are left with the myths of power. Theopoetics and myth and stories help us ask questions that will orient our ways of being. They are mystical and help us perform offerings, honor the living, honor the dead. Help us inspire and conspire. How do we heal the wound that is the lack of Love, Perez will ask us? How does one return from being violence, violated, betrayed, wounded, individually, socially, culturally, historically? With a plan for social justice, for carrying on through hope rather than despair? How and should we bounce back? It was in this mythical homeland that I saw our forebears and future kin. What is love and what does it want from us? Perez asks. She says that love is an ofrenda in the face of negation. An entity that is available to us at the crossings. A resurrection of dreams that found their ways into the flesh, returning, becoming, emerging, resurfacing, evoking.

Every poetic act of ours is a testimony to these other ways of being. Totalitarian regimes today are fond of giving us a clear map, defining visibility—no place for mystery for questions, for the generative darkness of the womb. No saudade, no desire that longs for another way of being. These images you have seen thus far are images of saudade, of a longing to be in a different way. They are ways of inventing worlds, of bewitching our experiences with other perspectives of feeling, doing, thinking.

I am thinking now that the Atlantic is a vast chamber through which many stories made their crossings. Deterritorialization, breaking down and apart of identities. Colonialism and imperialism created death, the extermination of peoples, of ways of knowing, of symbols. Peoples that were sequestered from their lands in the continent of Africa and disembarked in Brazil, for example, understood that death happened when forgetfulness was installed. Their commitments with ethics and aesthetics, their politics and their epistemologies, cosmo-logics and their spiritual practices had to walk hand in hand with creative acts, with their religiosity. In the Candomblé tradition, which was outlawed in Brazil through the 20th century, orixás enchanted the everyday transmuting stones, trees, rivers, at the sound of their drums. The earth, the forest continue to be homes to fields of possibilities, where rituals are performed and the somberness of disenchantment is driblado, dribbled. They dribble and transgress the colonial structures of power, offering ambiguity, a knowledge that lives in the interstices of western ways of knowing. As Simas and Rufino remind us: we must learn to read the poetics of Candomblé if we are to understand the politics of Candomblé. Tomorrow, in brazil, we celebrate São Jorge, Saint George. In Brazil, this saint is seen as the warrior, the ultimate activist who not only seeks but secures justice for all, by all means necessary.

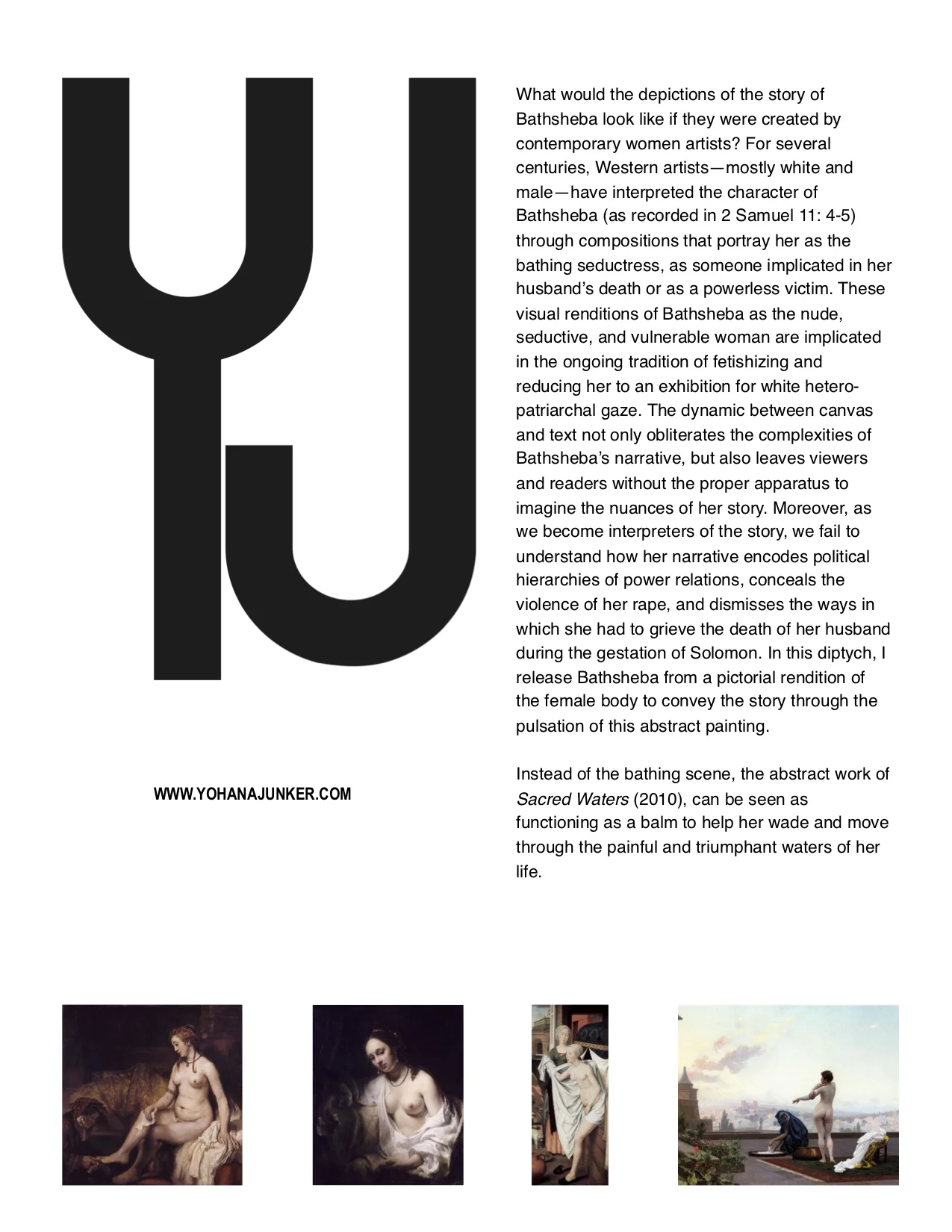

Luang Senegambia is a visual artist from brazil who lives and works in Rio de Janeiro. Since 2014 he has dedicated his art-making to interpreting Afro Brazilian religious traditions. His process involves coalescing in collages political realities, images and symbols that speak to being black in Brazil, and listening to songs that mark the syncopated rhythms of the orixás. Syncope is an unexpected alteration in the rhythm, an interruption of the regular flow of rhythms. A placement of rhythmic stresses or accents in unexpected places. Simas and Rufino speak of syncope as breaking constant, predictable sequences in music, giving us a glimpse of the void, of the emptiness, of silence. Syncope is at work here in this artwork. We expect Sao Jorge and Luang Senegambia gives us Ogum. Responsible for bringing the earth into being, for the secrets of iron, for being a warrior of justice for all, Ogum is an important orixá in Brazil.

In this other work, Luang Senegambia is centering the story of the Brazilian council woman Marielle Franco who was elected by the city of Rio de Janeiro and was brutally executed on March 14th, 2018. As a black, lesbian, single mother—born and raised in the Maré favela—she worked against racism, inequality, and homophobia in a country mired by the consequences of white supremacy, hetero-patriarchy, feminicide, and neo-capitalism. We see Franco here syncopated with Oyá the female warrior orixá who rules the rays, the winds, and tempests. Eparrei oya. She seeks justice for all, carries a sword. She dances snd from her swirls winds of change are created. She has the right to bear a sword to protect her children in the world, and when needed to assumes the form of a buffalo who is ready for battle.

In some of these dreams and stories, Oyá encounters Ormolu. He’s dressed in straws as if to hide his body. There is shame all around. No woman wanted to dance with him, except for Oyá, who wanted to have a dance with this orixá from the earth. Oyá lifted the straws and discovered that Omolu was beautiful. Sure, his body was covered in dis-ease, with open wounds. And yet. He was beautiful. The story goes that Oyá breathed wind unto his skin and his disease became popcorn that fell onto the grounds. Omolu controls the cycles of diseases and cures, especially during pandemic like the ones we are living through. He reminds us that many are the healing cycles of the earth and that it offers itself to us, so long as we are willing to access its ways of knowings and cosmo-logics. You see, knowledge systems that are closely linked to the earth have emphasized for millennia that there is no “out there,” we are all inter-related, inter-connected, complicit, and accountable to all of our crisis. And being so, we must apprehend this moment, weaving together perception, emotion, imagination, bodies, and action,” bringing back to our body-knowledge that which is invisible. To religious traditions across the planet this is precisely the task of providing a witness to, of offering a testimony, of ritualizing, of creating acts of mourning, and worship, and gratitude, with the arts, music, and imagination.

As Octavia Butler has put it, “the very act of trying to look ahead to discern possibilities and offer warnings is in itself an act of hope.” Spiritual teachings, social consciousness, and our social gospels, as Butler has puts it, expand our notions of solidarity, redefine and rediscover the human spirit, and devolve us to our bodies. The images we have seen today, the music shared by Jeff Chang and Calvin Williams and these images that created a visual narrative they illuminate into the past and the present and the future towards forms of life that are worth living. A world without capitalism, prisons, violence. A world that is ours to imagine, speculate, rehearse, create. As Andrianne Maree Brown has told us, there are multiple and multivocal worlds inside of us. Can the murmur of our collective efforts be heard across time, and space, and place and tradition? Can we fossilize capitalism? Compost our longings and desires so they keep birthing other worlds into being? I sure hope so, Dear Comrades. Our visions must be layered and cumulative, inscriptive, full of overlays of bodies, memories, histories, materials, mediums, genres, bodies, so that we work toward a presentism and away from forgetfulness. Death. Erasure. May we imagine, conjure, multiply, proliferate, find traction, and fight for visibility, resources, power, May we contest the privatization of our lives. The propertization of our relations. The high jacking of our rights to be and desire and love and create. May we vision, claim our spaces for action. May we confront, organize, run wild. May we stand in the power of our discourses, epistemes, cosmo-logics, religious and body-knowledge. May we create a world in our own terms, where all of us are free. And may this world be full of beauty, full of bodies that move, whether internally or physically or emotionally or spiritually. May we forge new images, stories, futures. Until we meet again. May we walk humbly, agitatingly, and softly upon this earth, in the company of those who visited in my dreams and those who are yet to be. May spirit breathe life into our tired bodies. Our tired eyes. And may we create. Create profusely. And dangerously.

In mutuality, and with affection,

Dr. Yô

[1] Ailton Krenak, Idéias para Adiar o Fim do Mundo (São Paulo: Compahia das Letras, 2019), 26–27.

[2] Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 8.

[3] Simpson, As We Have Always Done, 8.

[4] Simpson, As We Have Always Done, 9

![Foto da exposição de Flora Assumpção, Cativa [A natureza da natureza], Galeria Janete Costa, 2018. Fotografia: Flávio Lamenha.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56f1a16462cd940344281032/1522326128617-04NAKV52N1ZXNF7K8I77/Flora+Assumpcao_CATIVA_GJCosta_2018_22.JPG)

![Foto da exposição de Flora Assumpção, Cativa [A natureza da natureza], Galeria Janete Costa, 2018. Fotografia: Flávio Lamenha.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56f1a16462cd940344281032/1522326468932-N7Z1T1BJNRG4463L1LI1/Flora+Assumpcao_CATIVA_GJCosta_2018_19.JPG)

![Foto da exposição de Flora Assumpção, Cativa [A natureza da natureza], Galeria Janete Costa, 2018. Fotografia: Flávio Lamenha.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56f1a16462cd940344281032/1522326533896-KJ5E4P8JJ2B6DP7BI7TA/Flora+Assumpcao_CATIVA_GJCosta_2018_49+%281%29.JPG)

![Foto da exposição Cativa [A natureza da natureza], Galeria Janete Costa, 2018. Fotografia: Flávio Lamenha.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56f1a16462cd940344281032/1522326387576-ODQI6YK8SJJ7A7CDQ26N/Flora+Assumpcao_CATIVA_GJCosta_2018_33.JPG)

![Foto da exposição de Flora Assumpção, Cativa [A natureza da natureza], Galeria Janete Costa, 2018. Fotografia: Flávio Lamenha.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56f1a16462cd940344281032/1522326662098-V3HSXRJNJ6OPGAW288DJ/Flora+Assumpcao_CATIVA_GJCosta_2018_40.JPG)

![Foto da exposição de Flora Assumpção, Cativa [A natureza da natureza], Galeria Janete Costa, 2018. Fotografia: Flávio Lamenha.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56f1a16462cd940344281032/1522326586380-UNVXJ1FT30C4RC3PEO4B/Flora+Assumpcao_CATIVA_GJCosta_2018_37.JPG)

![Foto da exposição de Flora Assumpção, Cativa [A natureza da natureza], Galeria Janete Costa, 2018. Fotografia: Flávio Lamenha.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56f1a16462cd940344281032/1522326756172-YOV1VSZ41J3CGU40NKAH/image-asset.jpeg)